The Bash Primer

If you're interested in just the Unix tools we've used so far, there's a separate page for that.

About Bash and the prompt

Main article: An overview of Bash and the interactive prompt

At a glance:

What is bash

Bash (which stands for Bourne again Shell) is the name of the shell program that interprets our text input and converts it into commands for the computer to run. Each time we type in a command, hit Enter, Bash evaluates/executes the command, and then prompts us for the next command.

What is the prompt

The prompt is what Bash uses to signal that it is waiting for your next command. Prompts can be customized. For most of the examples listed on the site, the prompt will look like this:

user@host:~$

I try to preserve what the code (and its output) looks like at the prompt, which means that you cannot just copy-and-paste examples like this:

user@host:~$ for i in $items; do

echo $i

done

Text, quotes, and literal values

Main article: Text interpretation in Bash

At a glance:

Multi-line execution

For readability sake, users can separate a length command into multiple lines by appending a backslash after each line:

user@host:~$ mkdir -p January February March April \

May June July August September October November \

December

Multiple commands per line

For readability sake, users can use semicolons to indicate the end of a command within a single line. This allows the user to list and execute multiple commands upon hitting Enter:

user@host:~$ mkdir -p January; mkdir -p December

Multiple conditional commands per line

The use of double-ampersands between commands will also allow the execution of multiple commands in a single line. However, unlike semicolons, if the first command fails, the second command will not run:

user@host:~$ cd some_directory_that_may_exist && rm -f *

Literal text strings with quotes

The use of quotes allows the user to enclose a text string as a literal value. For example, the following will create a single directory named 'Documents and Settings'

user@host:~$ mkdir 'Documents and Settings'

Without quotes, the same command would create three directories: Documents, and, and Settings

user@host:~$ mkdir Documents and Settings

Special characters with double-quotes

Either single-quotes (apostrophes) or double-quotes (quotation marks) can be used to enclose a literal string:

user@host:~$ echo 'Jimmy says "Hello"'

Jimmy says "Hello"

user@host:~$ echo "Jimmy's friend does not respond"

Jimmy's friend does not respond

However, if a double-quoted string encloses a special character, such as the dollar-sign that denotes a variable, the shell will expand the variable to its value:

user@host:~$ some_number=42

user@host:~$ echo 'There are $s bottles of beer'

There are $some_number bottles of beer

user@host:~$ echo "There are $some_number bottles of beer"

There are 42 bottles of beer

Using heredocs

Vital to know for multi-line strings:

cat > stuff.html <<EOF

<html>

<h1>

<a href="http://example.com">An example</a>

</h1>

</html>

EOF

Command syntax

Main article: Introduction to command syntax and execution

At a glance:

Arguments

Many commands take space-separated arguments. For example, the mkdir takes in one or more arguments and will create a new directory for each one:

user@host:~$ mkdir apples oranges 'Documents and Settings'

Filename arguments

Some programs, such as cat, grep, and wc, will interpret arguments as referring to names of existing files to open and process:

wc existing.file.txt

Contrast this to echo, which does not interpret its arguments as filenames:

user@host:~$ echo echo echo "Ok enough with the echoes"

echo echo Ok enough with the echoes

user@host:~$ echo filename.txt

filename.txt

Options

Many commands have options (also referred to as flags), to allow the user to customize the functionality. For example, curl takes in a URL as an argument and will download the file at that URL to standard output. However, the user can use the --output option to specify a filename to save to:

user@host:~$ curl http://www.example.com --output myfile.txt

Aliased options

Many command options have shorthand aliases. For curl, --output and --silent can be referred to as -o and -s, respectively:

user@host:~$ curl http://www.example.com --output myfile.txt --silent

user@host:~$ curl http://www.example.com -o myfile.txt -s

Commands are unique

Every command has its own origin story, and consequently, its own options and arguments and rules of behavior. Do not think that the behavior and options of one command translates to another:

user@host:~$ curl -vo test.html "www.example.com"

user@host:~$ grep -vo test.html "www.example.com"

The man page

You will never be able to memorize all the combinations. But remember what commands can do, and then look up the documentation.

Use man, followed by the name of a command, to retrieve its documentation. You may find it easier just to do a Google search for a command's name.

user@host:~$ man grep

Pipes and Redirection

Main article: Pipes and Redirection

At a glance:

Using a pipe to redirect standard output (stdout)

user@host:~$ cat file.txt | sort

Redirecting stdout into a new file

user@host:~$ sort file.txt > sorted.txt

Redirecting stdout and appending to a file

user@host:~$ head -n 10 a.txt >> all.txt

user@host:~$ head -n 10 b.txt >> all.txt

Variables and command substitution

Main article: Variables and command substitution

At a glance:

Setting a variable

user@host:~$ some_val="Some value"

Referencing a variable's value

user@host:~$ echo "This is $some_val"

This is Some value

Command substitution

user@host:~$ nums=$(seq 1 3)

user@host:~$ echo "My favorite numbers: $nums"

My favorite numbers: 1

2

3

Arithmetic in the shell

user@host:~$ x=$((99 + 1))

user@host:~$ y=$(( 10 + x))

user@host:~$ echo $y

110

Loops

Main article: For and Read-While Loops

At a glance:

Basic for loop

user@host:~$ for item in $items;

do

echo $item

done

For loop through a number sequence

user@host:~$ for x in $(seq 1 100);

do

echo $x

done

Read-while loop from a file

user@host:~$ while read line

do

echo $line

done < file

Shell scripts

Main article: Running shell scripts from Bash

At a glance:

Opening the nano text editor

user@host:~$ nano somefile.sh

Executing a script from the command-line

user@host:~$ bash somefile.sh

Giving a script executable permissions

user@host:~$ chmod a+x somefile.sh

Executing an executable script

user@host:~$ ./somefile.sh

Conditional branching

Main article: Basic conditional branching with if-then statements

At a glance:

Basic if/then syntax

user@host:~$ if [[ $text1 == $text2 ]]

then

echo "These are equal"

fi

Basic if/else syntax

user@host:~$ if [[ $text1 == $text2 ]]

then

echo "These are equal"

else

echo "These are not equal"

fi

Basic if/elif/else syntax

user@host:~$ if [[ $text1 == $text2 ]]

then

echo "These are equal"

elif [[ $text1 > $text2 ]]

then

echo "$text1 alphabetically precedes $text2"

else

echo "These are not equal"

fi

While loop that runs until a counter reaches 0

user@host:~$ c=10

user@host:~$ while [[ $c -gt 0 ]]; do

echo "The countdown is $c"

c=$((c - 1))

done

An infinite loop

user@host:~$ while [[ 1 -eq 1 ]]; do

echo 'FYI, 1 is still equal to 1'

done

The most important thing to remember

If you are reading this and are currently a Stanford student: Every time you close your laptop and re-open it. Or switch away from Terminal to check Facebook. Or switch away from one Terminal window to another Terminal window. Or step away for 10 seconds to get a drink of water. Or blink for longer than 5 seconds…

– The very next command you should run at the Terminal prompt should be:

hostname

Does it include corn and stanford.edu? If not, then you may be messing with the files and directories of your own computer, which is not required or recommended for the scope of the CompCiv class.

rm -rf will ruin you

Top-line summary: For the purposes of this class, never, ever run rm -rf in an automated script. In fact, just to be safe, don't even run it manually, especially on your personal computer. If you need to remove a directory, use rmdir, which will error out if that directory is not empty.

Remember the story about Pixar wiping out all of Toy Story 2 with rm -rf *?

rm -rf tells the Unix shell to remove files, by force, and recursively (i.e. any subdirectories in a target directory), without asking questions or confirmation.

If Pixar could accidentally rm -rf a movie with a production budget of $90 million, you should assume that you, a novice user of Unix, will do just as much damage to yourself. rm -rf is a heartless, nihilistic command that does not care what your directory contains – whether it's just your homework, every photo and document you've ever created, or a blockbuster animated movie – before completely obliterating it.

Here are a few of the ways you could screw up when running rm -rf, either manually or in an automated script:

- You thought you were logged into a remote computer rather than your own computer

- You thought you were in a directory that's safe to wipe out

- You thought a variable (referring to a directory name) has actually been set

- You didn't think a directory had a space in its name

- You make just a single typo

- Or another typo

- You made a typo earlier when creating a directory

- You were not the user you thought you were

For the homework, there will rarely be steps that require you to delete anything, even a single file, via an automated script. And there should never be a time when you need to run rm -r, nevermind rm -rf – email me first before you think to include it any script.

If you are rm'ing files manually, at the very least, take a second and execute:

hostname && pwd && whoami

Do any of those indicate that you are on your own personal computer (rather than Stanford's shared computing, or a cloud server)? Then maybe stop what you are doing.

Finding out your place in the Matrix

Very little in this course requires you to be in a rush. So before you do any major task, stop and do these steps:

Do you know what computer you are currently on?

-

Run

hostnameto see what machine you're on. If you are on Stanford's Farmshare, the response should be something like:corn10.stanford.eduAnything else, and you're probably operating from your own OS X or Linux machine.

-

Run

whoamito see who you're logged in as. If you're oncorn.stanford.edu, the response will be your SUnet ID. -

Run

pwd(print working directory) to see where in the file system you are. If you've just logged intocorn.stanford.edu, you should be in your home directory:/afs/.ir/users/y/o/your_sunet_id -

Run

lsto list the files in the directory

Alter your prompt

By default, your bash prompt on corn.stanford.edu looks something like this:

dun@corn24:~$

Perhaps you'd like it to be a little more obvious about what system you're currently on. To customize your corn.stanford.edu prompt, use nano to open and edit the file, ~/.bashrc

Once inside ~/.bashrc, go to the bottom of the file and add this variable assignment:

PS1='[GO CARDNIAL (°<°)]\u@\h:\w\$ '

(if you read through ~/.bashrc, you'll see that PS1 is assigned a value earlier in the file. Your new line will overwrite that value, so if you don't like what you've done, just delete your line from ~/.bashrc)

After exiting nano and saving your changes, you have to restart your shell in order for the changes to take effect. You can either just logout and log back in, or run this command:

source ~/.bashrc

Your shell should now be updated with this prompt:

[GO CARDNIAL (°<°)]dun@corn25:~$

If you want something a little more emotive, check out this list of Japanese Kaomoji, and re-open ~/.bashrc and re-edit your variable assignment of PS1 accordingly:

PS1='(BRING IT!> ლ(ಠ_ಠლ) \u@\h:\w\$ '

Like colors? Follow the patterns in this guide.

Use variables and string interpolation to organize the pieces

If you're adding lots of colors and emoji to your prompt, it may be easier to break it up into different variables, and then combine them into PS1

For example:

PS_SHRUGGY_GUY='¯\_(ツ)_/¯'

PS_HEART='♡'

PS_STUFF='\u@\h:\w\$ '

# Colors

BIRed='\e[1;91m'

BIPurple='\e[1;95m'

Black='\e[0;30m'

## All together

PS1="$BIPurple$PS_SHRUGGY_GUY$BIRed$PS_HEART $Black$PS_STUFF"

Do you find yourself typing over the prompt (i.e having a line-wrapping issue) because you loaded it with Japanese characters? Check out this solution on StackOverflow

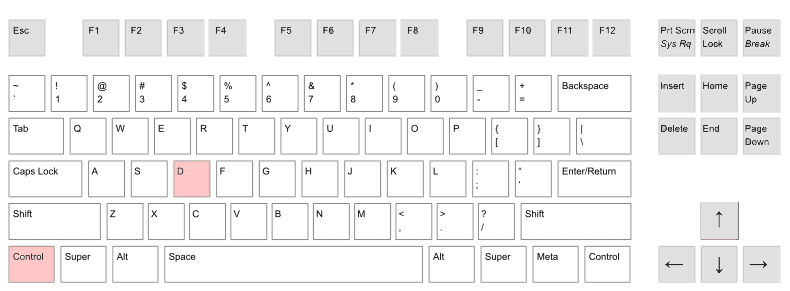

Keyboard Bash Shortcuts

In descending order of importance. Note that these only work at the standard prompt. If you're in a program like the nano text editor, then you have a whole different set of shortcuts to learn.

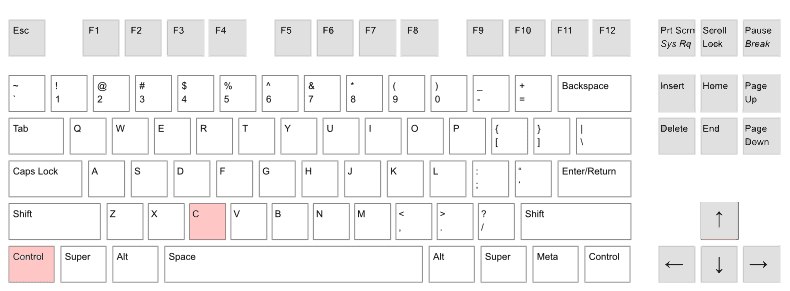

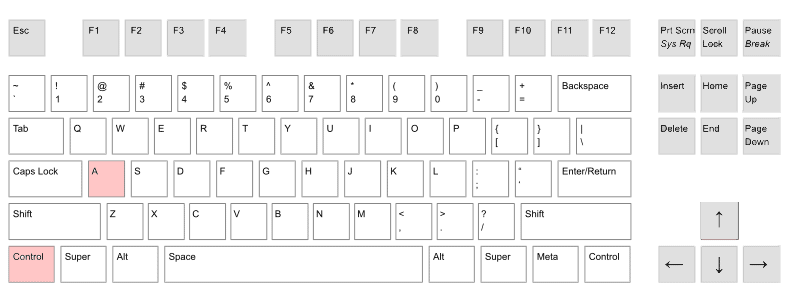

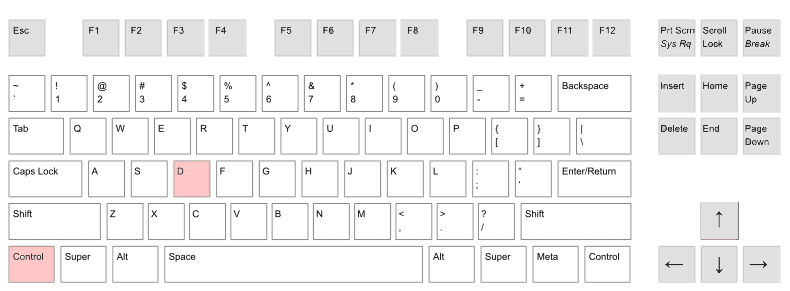

Ctrl-C - Kill process

This breaks/kills whatever program or command that you're currently running. If you ever get stuck in a loop, or a berzerking program, or just don't know why your prompt isn't responding to any input, hit Ctrl-C a few times.

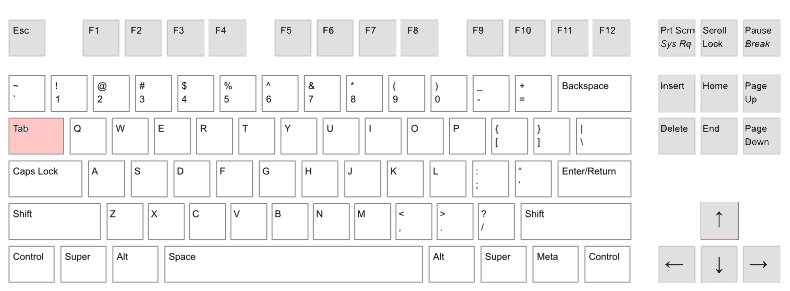

Tab - Autocomplete

This will attempt to autocomplete the name of a file or program based on what you've typed in so far. If there are multiple possibilities, hitting Tab twice will list them.

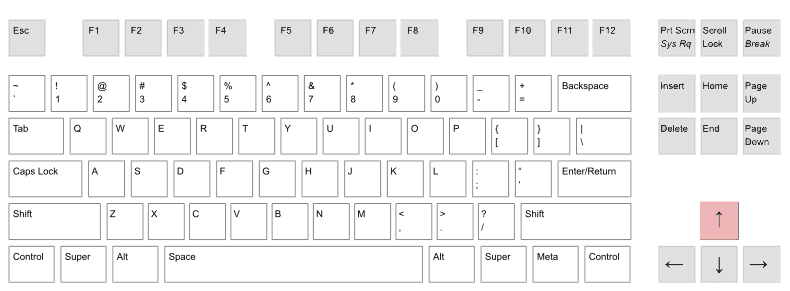

Up - Go backwards in history

This will cycle backwards through your history of commands. Handy for re-running a previous command in which you want to change one variable/typo.

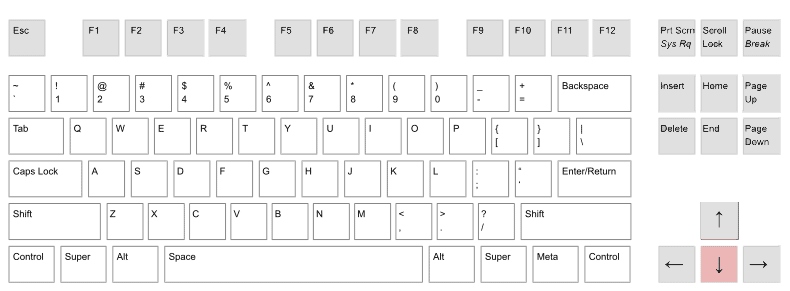

Down - Go forward in history

The opposite of Up.

Ctrl-A - Move cursor to start

When at the prompt, this shortcut will bring your cursor to the beginning of the current line. Handy for when you need to fix a typo before hitting Enter.

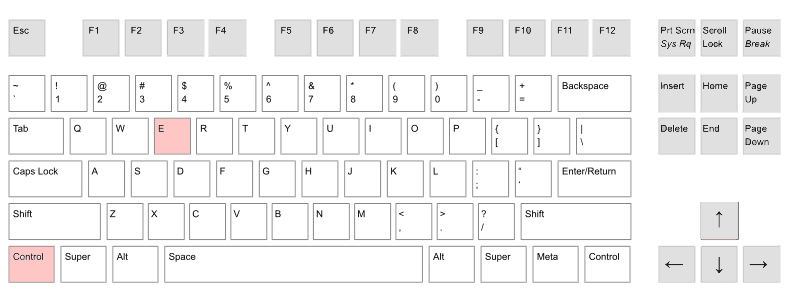

Ctrl-E - Move cursor to end

The opposite of Ctrl-A; this brings you to the end of the current line.

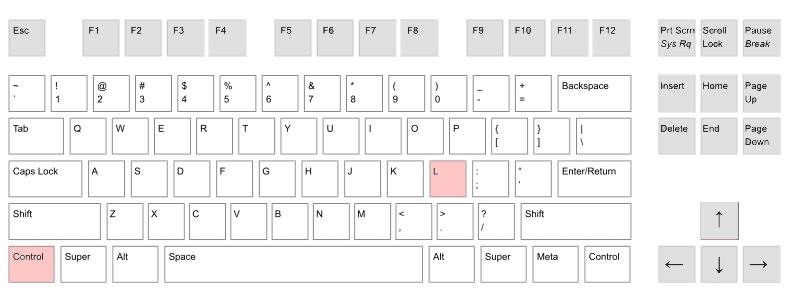

Ctrl-L - Clear screen

This clears the screen, handy for after a program has just dumped a bunch of data into standard output.

Ctrl-Z - Suspend process

If you've just executed a long-running process, Ctrl-Z will suspend it and return you to the prompt. At this point, you can type in bg to have the process run in the background. Or use fg to have the process continue running in the foreground.

Ctrl-D - Exit shell

If you are at the standard prompt, this will cause you to log out. If you're typing into a program via standard input (e.g. mail), and hitting Enter only create new lines, use Ctrl-D to exit back into the standard prompt.

Navigating the file system

How to get around the Unix filesystem.

Commands for moving around directories

pwdto show the name of the current directorylsto list files in the current directorycdto change directorymkdirto create directories

Example usage

cd ~- Jump to your home directory.cd /- Jump to the root directory, (something that you should almost never have to do)cd ..- Move to the parent directorycd ../..- Move up through two directoriesmkdir -p /tmp/hello/this/is/fun- Create a new directory and all of its parent directories as necessary (i.e. the-poption)cd -, equivalent tocd $OLDPWD, i.e. it returns you to whatever directory you were previously at.

Transferring files

Note: These instructions are for OS X/Linux users.

If you have a file on your own computer that you'd like to move to a remote computer, such as to corn.stanford.edu, you can use the scp file transfer program. When running scp, you'll be asked to enter your SUnet password (as if you were just SSHing in):

Download a file from corn.stanford.edu to your own computer

# usage: scp account@remote.machine.com:/remote/path local_path

scp your_sunet@corn.stanford.edu:~/some/path/data.txt ~/Downloads/data.txt

Upload a file from your own computer to corn.stanford.edu

# usage: scp local_path account@remote.machine.com:/remote/path

scp ~/Uploads/data.txt your_sunet@corn.stanford.edu:~/some/path/data.txt

Resources

System set-up

If you are a pre-2012 Stanford student

Before 2012, students were given tcsh as their "default shell". Afterwards, students were given bash. This code examples in this course assume that you will be using bash. You can email the Farmshare IT Group to have your default shell be changed to bash.

Authenticating yourself with Github

The git and Github workflow

When you've made changes to your compciv repo (i.e. project folder on corn.stanford.edu), here are the git commands to add, commit, and push changes to your master repo on Github.com:

# (assuming you're in the compciv folder)

git add --all

git commit -m 'Changing my code for fun'

git push

More information:

SSH authentication with Github

Note: I've deprecated this section. It will still "work", but it's a little inconvenient on corn.stanford.edu and may require you to re-run and re-configure the ssh-agent (yes, it's as boring as it sounds) every time you log back into corn.stanford.edu. These instructions will work from your personal computer, if for some reason you are cloning and pushing from your own computer instead of corn.stanford.edu

The whole process we undertook to generate a SSH key was so that we could connect to transfer files to Github from corn.stanford.edu…

You can verify if you're authenticated by running the following command when logged into corn.stanford.edu:

ssh -T git@github.com

# response from Github:

# Hi dannguyen! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access.

If you get a Permission denied (publickey)., it means you have to re-authenticate (but you shouldn't have to regenerate a keypair). You can re-authenticate with these steps (this is assuming you placed your key in ~/.ssh/compciv_id_rsa):

eval "$(ssh-agent -s)"

ssh-add ~/.ssh/compciv_id_rsa

# After this command, you'll be asked to enter your passphrase... this is NOT

# the same as your password for SUnet or for Github

If you've forgotten your passphrase, you can always repeat the keypair generation steps from the beginning. Just delete the existing ~/.ssh/compciv_id_rsa